The convenient lie: Apple, consumerism, and culpability

When the Penn State scandal broke several months ago and the depth of the cover-up was revealed, the cries of outrage were nearly drowned out by angry denials and gasps of disbelief. Residents of Happy Valley and Penn State fans throughout the country steadfastly refused to believe that Joe Paterno, head coach of forty-six years, would allow such a thing to happen under his watch. Further investigation and court documentation revealed the worst, or what we think is the worst. The Board of Trustees at Penn State fired Paterno, likely saving him from further revelations of impropriety.

The reason people were shocked is because Paterno has a previously unshakable reputation as a man of honor and integrity. He was a shining beacon in an ethically muddled NCAA. How exactly did he gain that reputation? Simple: because that’s what he and his handlers told people. Should that be enough? It is for most people, even though it shouldn’t be.

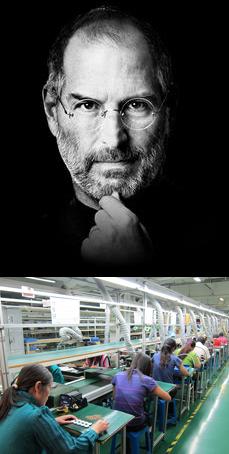

I was reminded of Paterno this morning when seeing reaction on Facebook to this week’s edition of the NPR program “This American Life,” which included an excerpt from writer and monologist Mike Daisey’s one-man show about Steve Jobs. The excerpt detailed the atrocious working conditions at Foxconn, the Chinese manufacturer responsible for making Apple products. Among the findings were crippling injuries, toxic exposure to unsafe chemicals, and children as young as twelve years old working at the plant.

The shock and dismay I saw expressed over the piece seemed genuine, just as it did with Paterno. Yet at least Penn State’s boosters had the excuse that they were not given any reason to suspect Paterno would help cover up pedophilia and child abuse. In the case of Apple and Chinese working conditions, though, there was plenty of precedence.

Did we really not know, or was (is) it just easier to pretend we didn’t?

When Steve Jobs died last month, deification from the media and inconsolable consumers made gripes about Apple’s use of sweatshops seem like the cynical mumblings of contrarians. The problem is that there’s plenty of documentation and reporting that supports the criticism. Apple’s own website makes its audits of plants like Foxconn available to the public. The reports detail the transgressions they encounter and try to remove themselves from culpability by noting actions taken to improve conditions. Yet we’d be aghast to read of the kind of conditions in a first world nation that Apple’s auditors respond to with the equivalent of a wag of a finger. In one example from their 2010 report, over 130 people sustained permanent injury from exposure to a chemical Foxconn knew was hazardous. Apple’s response was to give the company the chance to stop using the hazardous chemical with the threat of a follow-up audit.

That’s it. And it’s not enough.

Even more transparent is the apologist tone the piece on “This American Life” takes in its second act. Host Ira Glass brings in New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof to ease our consciences, which he is more to happy to do even while acknowledging the atrocities being committed for the sake of our own pleasure and convenience.

“There’s no doubt that it’s been a tremendous benefit,” Kristof said of the deplorable working conditions. His argument in the piece and for years has been that the type of terrible working conditions that Daisey and others have communicated to the West are somehow permissible as a lesser evil. Socially conscious, even, as he adds that companies like Foxconn “created massive employment opportunities, especially for young women.”

I find that reasoning specious to say the least. The idea that terrible working conditions is better than no working conditions at all is on the surface a valid observation, but it’s misguided if not intellectually dishonest. It’s based in a belief that the current circumstances are somehow the best that the Chinese government and corporations can do. Furthermore, Kristof invokes our own labor history and says it could take a hundred years for places like China to catch up, which completely discounts the exponential nature of technological, social, and cultural progress.

Kristof’s position is, I think, rooted in a genuine belief that things are bad but that we simply cannot confront it with traditional means (boycotts and so forth) without some tragic unintended consequences. He’s not alone in holding that belief. But I can’t help but feel that’s just another convenient lie we tell ourselves so that we can drift to sleep at night along beside the fading light of our idle iPhones.

The tone of the program is typical of NPR programming and reporting on human rights abuses, particularly those in which American consumers are in some way culpable. They want us to listen, so they don’t want to make us feel bad. They want us to pity the Chinese, but they don’t want us to feel guilty over it. Yet the simple fact of the matter is that things can be much better than they are. China’s oppressive communist regime and corporations in and outside of the country could improve conditions, but they choose not to out of convenience and concern for their bottom line.

Even Apple, with its ridiculous profit margin, could do even more than it already does. Unfortunately, we are a society that identifies with brands more than workers overseas for the simple fact that we can see and hold an iPhone, so we are far less likely to rail too hard against them even though deep down we are aware that they are capitalizing on a dire situation. It is an unfortunate but understandable oversight given the degrees of our removal from the situation. Apple deserves the scorn and bad press they’ll receive for this press. Part of the problem, though, is that we have been and continue to be far too eager to give them a greater status than they deserve simply because we like their products. We want to equate progressive ingenuity with humane practice, but they are not even related let alone mutually inclusive.

Another convenient lie.

That said, the problem is much bigger, literally and conceptually, than Apple. The root of it is that China, as their human rights record has shown, view their own people as an expendable resource. We’re all culpable – some of us more than others – but none more so than China itself. Is Apple reprehensible for taking advantage of this system? Yes. But as far as the Chinese government goes, these are their people.

But is there anything we can do about it? The honest, simple answer for those looking to consume with a clear conscience is to steadfastly refuse to buy anything made in China and make as much noise as possible about it on a large, organized, and mobilized scale. Unfortunately, our economy makes it very hard for any of us – myself included – to engage in such a radical departure from our regular spending habits and even day to day functioning.

Still, the very least we can do is call it out when we see it and make an effort to let companies like Apple know that they’re not doing enough, and especially to make as much noise as possible about the Chinese government (which has countless violations on its human rights record and regular evils committed by its government…and that’s just what we’re aware of). Maybe our President and other heads of state have to be polite for political reasons, but we sure don’t.

3 Responses to The convenient lie: Apple, consumerism, and culpability

Leave a Reply to Anonymous Cancel reply

Upcoming Events

There are no upcoming events.

Recent entries

- Goodbye, goodbye, goodbye…

- Listen to me LIVE as guest co-host of Alternative to Sleeping tonight at 10pm!

- Realtors: “WAAAAAAAAAHHHHHH” George Hearst III: “NONONOO SSSSHHH IT’S OKAY, it’s okay…here. Here’s a pacifier.” Kristi: “#oops.”

- Open Mic web series premiere tonight @ Lark Tavern

- Trust Me, You’re Going to Want to See This

on Twitter

Do you really mean “atypical” in your sixth graf from the end? I’d argue that it’s the opposite — that type of programming is completely typical.

I get where you are coming from but I respectfully disagree with you on some of the points. I think that rather than criticizing or almost condemning people for their outrage when you feel they should have known better, it’s better to embrace the fact that people are outraged. Does the outrage come too late? Probably, but that doesn’t mean it’s any less valid. The outrage provides an opportunity for galvanization. While Kristof might have his points, the fact that this story still raised outrage among people should be treated as a good thing, imho.

I struggle on a near daily basis with consumerism and how to put my money where my mouth is. It’s incredibly hard. As you correctly stated, our economy does make it very hard for us to engage in this. For instance, I’m a reporter. As such, I need to use technology on a daily basis and I need to do so in a way that seems to be the most effective and efficient. I’ve discovered that the iPhone is one of the best reporting tools out there – it allows me to take decent photos, videos and audio recordings, file stories quickly, find the information I need right away, get where I need to go, and a number of other aspects that are important to me. I use a MacBook Pro for similar reasons, although mine was purchased secondhand. Sometimes it’s a matter of balancing the evils. I don’t condone the behavior of the company, but using the product allows me to cover other atrocities and human rights issues on a smaller scale. I realize that the argument could be made that another product, such as the Android, could provide a similar service, but again, I’m using what I have found to be the best for my purposes. And rather pessimistically, I’m certain there are similar issues with other products and their development.

Technology definitely makes it very hard to be an ethical consumer. When it comes to the food I buy, or the clothing, I feel like it is far easier to use my consumer power, by purchasing locally-produced goods and items that come from small, independent companies whose values and goals I support.

(re: atypical vs. typical. You’re right and fixed. I initially wrote a different sentence than what appeared in the final version.)

I get what you’re saying, but I don’t think I condemned them for it. I remarked that the outrage and anger seemed genuine.

That said, I do think it’s valid to point out that these conditions are no secret to us. We know where our products come from and the conditions under which they’re manufactured. We make passive observations about it all the time. What I do think people should stop doing, though, is lending certain business/tech people and brands a higher ethical standing than they deserve. Which is exactly what happened with Apple. People like the iPhones and Macbooks because they’re great products. But then they turn around and grant the company and especially Jobs a wholly undeserved status as progressive and “the good guys” in the tech sector. It’s facetious, but worst of all, it allows them to get away with this sort of thing for as long as they have.

Outrage is good. But not what contributes to that outrage, which is misguided loyalty and affection for a product, its inventor(s), and its distributor(s). Especially with Apple; the joke was always that its users are like a cult, but in all seriousness, the unreciprocated emotional relationship human beings develop with companies like them is unhealthy and dangerous (not so much to us as to others). While most of us can’t help ourselves because of the model our economy and society is built on, we can and do have the ability to maintain something resembling a healthy level of skepticism about it.

We spent the better part of the 20th Century developing a culture with an emphasis on materialism. We have the tools at our disposal to receive and distribute information and awareness on a greater scale than ever before, but that can’t give us perspective on a day to day basis. The awe and reverence we give to companies and brands skews that in a very bad way, and it makes us all to eager to conveniently forget what kind of system we operate here and abroad.

I’ll give you the Apple adoration. Until a couple of years ago, my general policy on computer purchases was to buy whatever seemed most affordable, and I’m one of the few people I know who has actually kept cell phones until they no longer worked. I don’t really get too amped up about any particular brand, for the most part, and I definitely think the people who go all out and wear Apple attire, etc, are pretty weird. I once dated a guy who liked when I wore leopard print because it reminded him of the Apple OS that was currently in use. That was just one of many dealbreakers.